The Five Room Dungeon Expanded

My theory on designing expansive one-shot dungeons with a focus towards replayability

The Original Five Room Dungeon Method

Originally theorized by Johnn Four back in 2002-2003, this method has made a huge impact on GM’s, Game Designers, and the community as a whole. It certainly has helped me a ton in my development as a game designer and it’s important that I make sure John’s work is at the forefront of this discussion today.

Some of John’s key concepts I want to talk about and highlight are:

Flexible Size: five room is just a guideline, feel free to make them bigger.

Short: some players/GM’s dislike long dungeon crawls, having a short dungeon can keep things fun for all.

If you have never heard of the five-room dungeon before, you must absolutely check out: The Ultimate Guide to 5 Room Dungeons

Expanding the Five Room Dungeon

So, to get things started I want to preface this conversation by saying: I like big dungeons, I like creating a lot of rooms and ideas, but I also really like one-shot adventures. I also attend a good number of conventions and find myself replaying the same adventures over and over, so in addition to the above, I also like adventures with a lot of replayability.

Now here comes the hard part: How can we create large dungeons to be used in a one-shot; and how can we make them replayable?

After some testing, here is my answer to that question:

Pathing

Timers/Clocks

Event Tables

Let’s take a look at each of these and how I implement them into the dungeons I design.

WARNING: These methods I am about to share come with a big drawback: much of what you design may go unused if you are creating a dungeon to be played only once. This design theory is better used for folks trying to run dungeons multiple times for different groups, or for designing dungeons to be published and used by different GM’s who like one-shots and big maps. This method is also a lot more intensive and time consuming, but I have found it leads to excellent replayable maps for one-shot dungeon design.

Pathing

So, the five-room dungeon recommends 5 rooms because it is highly likely that the players will be able to move through all of these rooms within the allotted session time. But what if I want to make a dungeon with 20 rooms? How will my players be able to make their way through it within the allotted time? The unfortunate answer to that is: They won’t hit every room along the way.

But in saying that, we are making a dungeon to be big and replayable. So, it is okay if not every room is touched in every session; there will be another group and another session where they may find that secret passage that was missed before.

Onto the theory part: When designing this kind of dungeon, you need to determine a couple of things.

A starting point

An ending point

How many rooms total you want

How many rooms you want the players to cover on their path

From there you want to arrange the rooms in such a way, that the players can get from the start to the end within X number of rooms.

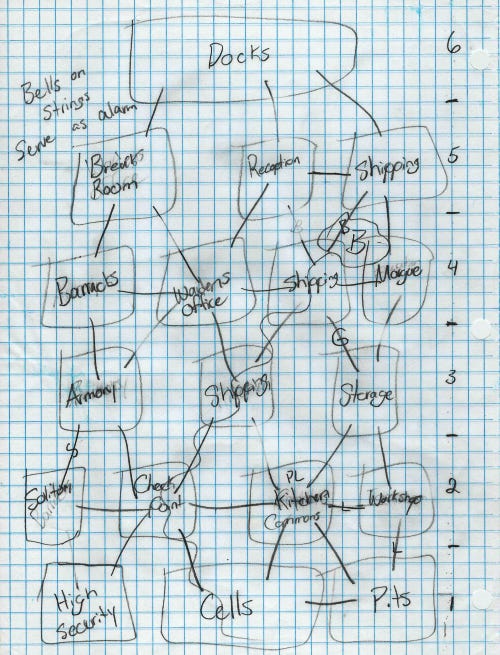

For example: I began working on an adventure for Peasantry called: Shackles and Sharkteeth. The players would Start locked up in cells and would need to escape the underground island prison at the End where the ships are loaded to leave the docks. I originally wanted about 15-20 rooms and wanted the players to pass through at least 6-8 rooms along the way. I then proceeded to lay a grid of the rooms and make connection points between them. Organizing them in a way that made sense for the prison layout.

Notice how I organized them into 6 rows, so that way the players had at the very least 6 rooms to pass through along the way. There are also a ton of forking paths meaning the players have tons of options.

Fast forward in time and I have completed the island prison map. Here is a gif showing 12 different routes through the prison. After some artistic liberties you will notice that each of the paths visits roughly 5-9 rooms, which was pretty close to my goal. Granted if the players end up backtracking, they could very well visit more rooms (there is very good reason for them not to backtrack, see more about that in the Timers/Clocks)

Here is another quick example: pulled from my adventure titled: Tiny Terrors where the peasants get shrunk down and sent into the heart of a tree to kill a termite queen. In this one there are three entrances into the tree, and the end location is the Queens throne. This one was better designed, 12 rooms, and players regularly hit 4-6 rooms. Plus, the sap river can throw players around a bit and create even more diverse roots (routes?).

Timers/Clocks

Everybody loves clocks! Have you even read Blades in the Dark? If you haven’t, please check out that link and see their excellent article on clock mechanics.

So, without diving too deeply into clock mechanics, I essentially use clocks to push and prod the players along their adventure and make sure the games pacing can get our one-shot complete on time. Here are a few different clocks I use:

In Tiny Terrors the clock takes the form of the shrinking spell wearing off. After 3 hours of real-time, if the players have not found and killed the termite queen, they begin to rapidly grow, potentially killing their characters and destroying the tree all in one go! The players are aware of their time limit, and it usually serves as a good incentive to move forward on their own. If they move too fast, I just slap more enemies in their way or hope they get swept away by the sap river current.

In Shackles and Sharkteeth, the players are racing against man-eating sharks and rapid flooding. I control the flood rate and # of sharks. If they move to slow, I can always push them along with more water. Too fast and they can fight more sharks and giant mantis shrimps. I can also trigger a water trap part way through for those who try to use the “quick way out” Here is a gif showing that:

Event Tables

The last thing I do to expand on the Five Room Dungeon is using large event tables that can randomize the events/quests/goals in the dungeon. These differ wildly from things like Encounters tables, because they don’t determine what you encounter, they determine what you need to accomplish.

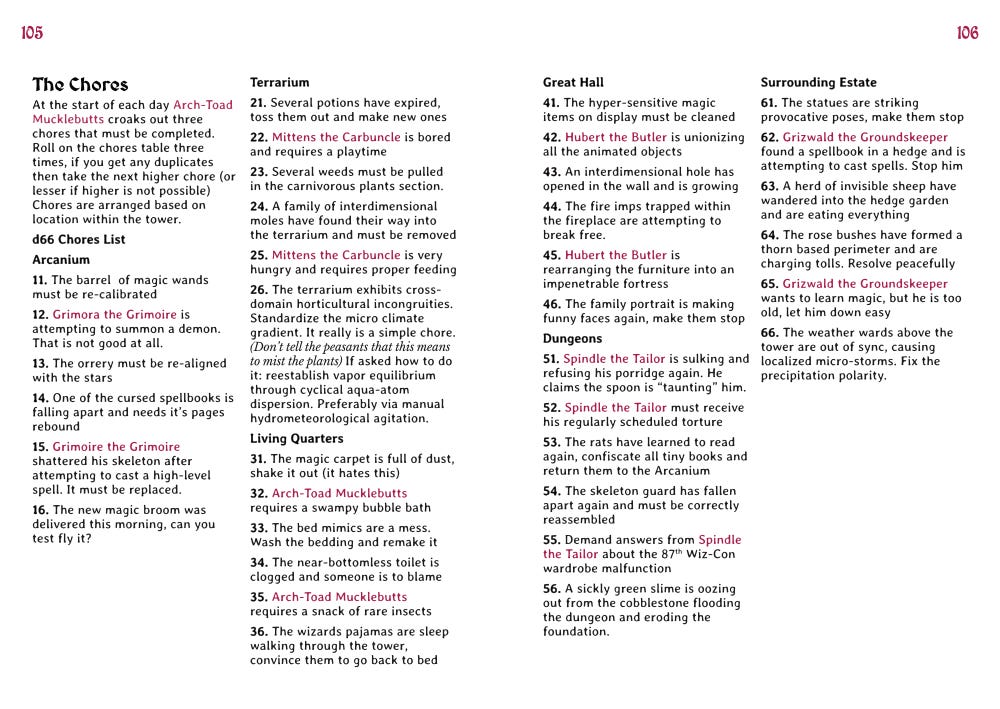

Here’s an Example: Another adventure I have been working on is A Wizard’s Sojourn. In this one the peasants are house sitting for a wizard for a few days. Every new day they must roll on this d66 table to determine what chores need to be done. The tower is only 6 locations big, but there are 36 different chores that could occur! On top of that, there is a separate list for Guests who visit the tower! While this five (6) room dungeon may not be expanded by its # of rooms, it is greatly expanded in its # of content and replayability due to these tables. These tables are also organized by locations. So, each location has 6 different possible chores.

I have a lot more thoughts on designing tables for replayability, but I haven’t quite finished those examples yet. I plan to dive into them in more depth on a later post of mine.

Wrapping it all up

So, I don’t think I articulated this blog post very well. But I hope the message of what I am working on has transferred into your noggin and resonates with you.

To recap, here are the big takeaways:

When designing large replayable dungeons to be used in one-shots, think about these things:

What paths/routes will the party be travelling? How does the dungeon layout cater to the pacing/replayability of your game?

How does your use of timers/clocks contribute to the story and help you finish on time?

How can we create event tables to diversify every venture into the dungeon? Even for those who may have played it before?

Thanks for reading, excited to build upon these ideas more as I design more dungeons and stress test my methods, perhaps I can formulate it into fewer, more digestible words.

Zakary Ellis

Note: at the time of writing this, none of these adventures have been released to the public yet. Working on getting the game published currently!